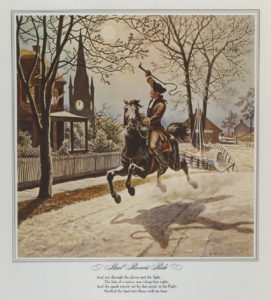

The Real Story of Paul Revere’s Ride

In 1774 and 1775, the Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Massachusetts Committee of Safety employed Paul Revere as an express rider to carry news, messages, and copies of important documents as far away as New York and Philadelphia.

On the evening of April 18, 1775, Dr. Joseph Warren summoned Paul Revere and gave him the task of riding to Lexington, Massachusetts, with the news that British soldiers stationed in Boston were about to march into the countryside northwest of the town. According to Warren, these troops planned to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two leaders of the Sons of Liberty, who were staying at a house in Lexington. It was thought they would then continue on to the town of Concord, to capture or destroy military stores — gunpowder, ammunition, and several cannon — that had been stockpiled there. In fact, the British troops had no orders to arrest anyone — Dr. Warren’s intelligence on this point was faulty — but they were very much on a major mission out of Boston. Revere contacted an unidentified friend (probably Robert Newman, the sexton of Christ Church in Boston’s North End) and instructed him to hold two lit lanterns in the tower of Christ Church (now called the Old North Church) as a signal to fellow Sons of Liberty across the Charles River in case Revere was unable to leave town.

On the evening of April 18, 1775, Dr. Joseph Warren summoned Paul Revere and gave him the task of riding to Lexington, Massachusetts, with the news that British soldiers stationed in Boston were about to march into the countryside northwest of the town. According to Warren, these troops planned to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two leaders of the Sons of Liberty, who were staying at a house in Lexington. It was thought they would then continue on to the town of Concord, to capture or destroy military stores — gunpowder, ammunition, and several cannon — that had been stockpiled there. In fact, the British troops had no orders to arrest anyone — Dr. Warren’s intelligence on this point was faulty — but they were very much on a major mission out of Boston. Revere contacted an unidentified friend (probably Robert Newman, the sexton of Christ Church in Boston’s North End) and instructed him to hold two lit lanterns in the tower of Christ Church (now called the Old North Church) as a signal to fellow Sons of Liberty across the Charles River in case Revere was unable to leave town.

The two lanterns were a predetermined signal stating that the British troops planned to row “by sea” across the Charles River to Cambridge, rather than march “by land” out Boston Neck.

Revere then stopped by his own house to pick up his boots and overcoat, and proceeded the short distance to Boston’s North End waterfront. There two friends rowed him across the river to Charlestown. Slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset in the darkness, Revere landed safely. After informing Colonel Conant and other local Sons of Liberty about recent events in Boston and verifying that they had seen his signals in the North Church tower, Revere borrowed a horse from John Larkin, a Charlestown merchant and a patriot sympathizer. While there, a member of the Committee of Safety named Richard Devens warned Revere that there were a number of British patrols in the area who might try to intercept him.

At about eleven o’clock Revere set off on horseback. After narrowly avoiding capture just outside of Charlestown, Revere changed his planned route and rode through Medford, where he alarmed Isaac Hall, the captain of the local militia, informing him of the British movements. He then alarmed almost all the houses from Medford, through Menotomy (today’s Arlington) — carefully avoiding the Royall Mansion whose property he rode through (Isaac Royall was a well-known Loyalist) — and arrived in Lexington sometime after midnight.

In Lexington, as he approached the house where Adams and Hancock were staying, Sergeant Monroe, acting as a guard outside the house, requested that he not make so much noise. “Noise!” cried Revere, “You’ll have noise enough before long. The regulars are coming out!” According to tradition, John Hancock, who was still awake, heard Revere’s voice and said “Come in, Revere! We’re not afraid of you”. He entered the house and delivered his message.

About half past twelve, William Dawes, who had traveled the longer land route out of Boston Neck, arrived in Lexington carrying the same message as Revere. After both men “refreshed themselves” (i.e. had something to eat and drink), they decided to continue on to Concord, Massachusetts, to verify that the military stores were properly dispersed and hidden away. A short distance outside of Lexington, they were overtaken by Dr. Samuel Prescott, who they determined was a fellow “high Son of Liberty.” A short time later, a British patrol intercepted all three men. Prescott and Dawes escaped; Revere was held for some time, questioned, and let go. Before he was released, however, his horse was confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Left alone on the road, Revere returned to Lexington on foot in time to witness the latter part of the battle on Lexington Green.

This story comes from several accounts written by Paul Revere after his Midnight Ride. To see one of them in his own handwriting, with a transcription, visit “Revere’s Own Words.” To find all the answers to your Midnight Ride questions, see our Frequently Asked Questions page.

For more information and an interactive map experience, view our Midnight Ride Map. You can also “Recreate the Ride” on your own!