A Model Society: Victorian Boston in the British Women’s Movement

Editor’s Note: As we approach the centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment’s passage, we are excited to present today’s guest scholar posting from Agnes Burt. Agnes’ work explores one of the lesser-known transatlantic struggles for women’s equality on the way to the vote, a battle in which Bostonians featured prominently on both sides of the ocean. This work continues our mission to examine the relationship between the U.S. and Britain, born of colonial structures, tested in the American Revolution and the War of 1812 and burnished during the World Wars. It instructs our interpretation of the Paul Revere House, its occupants, and its use over four centuries.

By: Agnes Burt, PhD

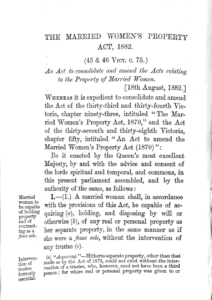

Conybeare, Charles Augustus Vansittart, and William Raeburn St. Clair Andrew. The Married Women’s Property Act, 1882, Together with the Acts of 1870 and 1874, with Introductory Chapter, Notes and Appendix. London: Henry Sweet, 1882.

In 2018, Britons celebrated the centennial of the passage of the 1918 Representation of the People Act—the Act granting women in Britain the right to vote in Parliamentary elections.[1] In just a few weeks, Americans will celebrate the centenary of the 19th Amendment, which guaranteed women’s voting rights. The passage of each of these laws marked the culmination of campaigns originating in the nineteenth century to enfranchise women on the same terms as men. While it was the most public aspect of the early women’s movement, women’s suffrage constituted one objective in a broader platform of social, legal and economic reforms advanced by an international network of Victorian-era activists who aimed to improve women’s lives. Through their advocacy, many Boston-based activists played a prominent role in British reform campaigns: portraying Massachusetts as a model of social progress that Britons could emulate, these Bostonians ultimately influenced reform efforts on both sides of the Atlantic.

Beginning in the mid-19th century, Victorian reformers began to advocate for legal changes that would reform a married woman’s status under the English common law of coverture. In addition to comprising a body of law in England, the common law also formed the foundation of many U.S. states’ legal systems—a legacy of their origins as British colonies. Under the common law of coverture, a wife’s legal identity was subsumed into her husband’s: upon marriage, a husband became the legal owner of his wife’s property (for example, income, furniture, jewelry, or livestock); any subsequent income a wife earned was legally her husband’s and could be taken to pay his debts. In 1848, New York became the first state to grant married women control over their property, with Massachusetts following its border state in the next decade. By 1870, when Britain’s Parliament passed a Married Women’s Property Act granting married women limited property rights in Britain, eighteen states in the United States had already passed laws granting married women control over their property.

The legal changes introduced in various states during the 1850s and 1860s provided a compelling model for British reformers in the 1870s as they continued to advocate for reform. Sympathetic witnesses from Vermont, New York and Massachusetts testified before Parliament attesting to the social benefits that their states gained from property law reform. In particular, English reformers imagined Massachusetts, which had introduced significant reforms in 1855, as the society that most closely resembled their own. For instance, the feminist periodical Englishwoman’s Review of Social and Industrial Questions, observed that no other state in America retained “so close a family resemblance in its social life to England.” Massachusetts – one of England’s first colonies in North America – could “safely be held up as an example.”[2] Massachusetts, the editor noted, “started with English laws, and has proceeded in our British fashion, not violently changing, but mending, patching, and remodeling the old laws, till … the fabric of the laws has been almost entirely changed through repeated amendments.”[3] Consequently, testimonies from Boston legal experts – lawyers, judges, and Harvard law professors – regarding the success of the state’s reforms played an important role in shaping British imaginings of the social progress to be gained by granting married women control over their property.

Bostonians’ testimonies to Parliament reinforced perceptions regarding Massachusetts’ and England’s commonalities. In 1868, for instance, the Parliamentary committee organized to investigate the question of property reform invited the Boston barrister Clement Hugh Hill, then residing in England while recovering from illness, to speak about the impact of reform in his home state. In his testimony, Hill explained that New England remained a conservative region relative to the progressive states in the western U.S.[4] Even among the New England states, he emphasized, Massachusetts was the most conservative. Given that the committee members had assembled a lineup of sympathetic witnesses from Britain and the United States to reinforce the need for reform, such a characterization was likely intended to reassure British conservatives that property reform was not a radical cause.

Hill’s testimony, as well as supporting letters sent by leading Boston legal figures, consistently extolled the social benefits that followed from legal reform, affirming British reformers’ arguments. Activists argued that the common law penalized working class married women because it permitted husbands to take their wives’ hard-earned wages and spend the money on alcohol instead of food for the family. Granting married women property rights, they asserted, would protect working women’s earnings from their husbands, allow mothers to provide for their children, and ideally, encourage working class men to treat their wives with greater respect. J. Wells, Associate Judge for the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, reinforced such claims when he wrote that in his experience, the law’s chief benefit was giving poor women the “power” to “control the fruits of their labor” from their husbands, who he characterized as “idle vagabond[s].”[5] Similarly, Hill emphasized that the law proved enormously beneficial among recently arrived “foreigners” because it inspired them to treat their wives with greater respect.[6]

Such positive testimonies provided a way for British reformers to counter their opponents’ claims that granting married women property rights would create dissension between husbands and wives and undermine social stability. While most Britons agreed that some minor reforms should be introduced to help poor women feed their families, opponents balked at any legal reform that appeared to overturn the principle of coverture – a wife’s legal subordination. They argued that granting married women property rights would inspire financial disagreements between spouses and lead to familial discord, undermining the domestic family harmony Victorians idealized as forming the foundation of their society. Subsequently, when Hill asserted that divorce rates and violence between spouses had decreased in Massachusetts, he challenged conservatives’ predictions that property reform would create domestic unrest.

Having observed these social benefits, all witnesses affirmed, no one in Massachusetts desired to return to the common law of coverture. Emory Washburn, a Harvard Law professor and the last Whig governor of Massachusetts, admitted that while he had initially regarded Massachusetts’ first “inroad upon the common law … with apprehension,” he would not support restoring the law if given the option.[7] Such sentiments were reinforced by others: George Stillman Hillard, a U.S. District attorney and eventual first dean of Boston University School of Law, as well as the anti-Imperialist activist and cotton manufacturer Edward Atkinson confirmed that “the only effects of our law have been beneficial.”[8]

Glowing testimonies about the benefits of property reform in the U.S. did not convince all Britons, however. One newspaper, the Pall Mall Gazette, suspected that such testimonies were not fully honest. “Can anyone who knows anything of Americans, of all people in the world, believe that an American would be likely to come forward before an English Parliamentary Committee and say: one of the most characteristic of our alterations in the law of England has not been justified?” one article asked. In this case, Britain and the U.S.’s long history was a reason to question Americans’ experiences. The paper doubted that any American would ever concede that “American women are not such good wives as Englishwomen, nor are American homes so happy as English homes.”[9]

Ultimately, while comparisons between the United States and Britain inspired anxieties about the relationship between the two countries, legal changes implemented in states like Massachusetts, filtered through Boston reformers’ representations of their state, offered British activists a useful model to turn to as they advocated for similar reforms. These transnational exchanges between liberals in Boston and England highlight how Victorians measured social progress through comparisons with other societies, a legacy the contemporary women’s movement continues. Feminists today, for instance, might emphasize the benefits experienced by women in Europe as a result of generous maternity leave policies when advocating for legislation redressing the scarce options available to women in the U.S. Many centuries later, while the object of reform may have changed, advocates for women’s rights continue to look across the ocean as they imagine what progress will look like.

Agnes Burt is a historian whose research focuses on women and gender in the Victorian age. She received her Ph.D. dissertation from Boston University which is entitled “Reforming the Married State: Women and Property after the Married Women’s Property Acts, 1870-1935.”

[1] Not all women were allowed to vote under the Act’s terms; the 1918 Act enfranchised women over thirty who met the appropriate property qualifications. In 1928, ten years later, women were granted the ability to vote on the same terms as men.

[2] “Art I. Legal Condition of Women in Massachusetts,” The Englishwoman’s Review, (March 15, 1876), 97.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Special Report from the Select Committee on Married Women’s Property Bill; Together with the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, Appendix, and Index (House of Commons, 1868), 58.

[5] Ibid., 86.

[6] Ibid., 58.

[7] Ibid., 85.

[8] Ibid., 87.

[9] “The Property of Married Women,” The Pall Mall Gazette, July 29, 1868.