“Horrid Scenes of Villainy”: The Stamp Act Protest of August 1765

By Nina Rodwin

August 14, 1765, most likely began as a typical day for Paul Revere. As he went about the day’s work at his silversmith shop on Clark’s Wharf, Revere was probably unaware that a crowd had hung an effigy of Andrew Oliver, Boston’s official Stamp Act collector, in the early hours of the morning. Maybe Revere overheard his customers discussing the incident during the day, as the news quickly spread throughout town. By nightfall, a large crowd took the effigy down from what would become known as The Liberty Tree and then paraded through the town. The crowd soon arrived at Oliver’s home and burned the effigy, minutes after his family made a narrow escape. Oliver soon after officially resigned his post. However, the fury towards the proposed Stamp Act was not quelled.

August 14, 1765, most likely began as a typical day for Paul Revere. As he went about the day’s work at his silversmith shop on Clark’s Wharf, Revere was probably unaware that a crowd had hung an effigy of Andrew Oliver, Boston’s official Stamp Act collector, in the early hours of the morning. Maybe Revere overheard his customers discussing the incident during the day, as the news quickly spread throughout town. By nightfall, a large crowd took the effigy down from what would become known as The Liberty Tree and then paraded through the town. The crowd soon arrived at Oliver’s home and burned the effigy, minutes after his family made a narrow escape. Oliver soon after officially resigned his post. However, the fury towards the proposed Stamp Act was not quelled.

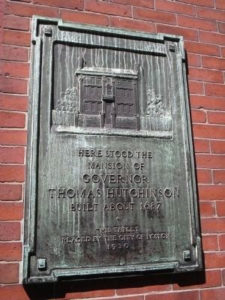

Just twelve days later, on August 26th, an enormous crowd surrounded the three-story mansion of Lieutenant Governor and Chief Justice Thomas Hutchinson. In only a few hours, the house was completely destroyed, expensive furnishings, textiles, wine, and silver were stolen, and even Hutchinson’s garden was razed to the ground. Over the next days and weeks, the people of Boston debated what this violent protest would mean for their movement. Could a large protesting group create real and desired changes? Or would an unruly mob threaten the very cause they fought for? As recent protests against racism, police brutality, and economic regulations have shown, the question of how to protest still remains to this day. While there are no easy answers to this question, we can make connections to how Bostonians reacted to the Stamp Act crisis and the contemporary reactions to violence and looting during our ongoing protests.

When Thomas Hutchinson saw his brother-in-law Oliver’s effigy at the corner of Orange (now Washington) and Essex Streets in August 1765, he immediately summoned the sheriff to cut it down, but was unsuccessful, due to the size of the “amazing mob.”[1] As the crowd moved towards Oliver’s dock and demolished a newly constructed brick building rumored to become a “stamp office,” he ran to warn Oliver’s family their home could be in danger. After Oliver’s family escaped, Hutchinson heard rumors that his home would be attacked next. Around 9:00 pm, Hutchinson quickly boarded up his door and windows, as a few hundred people marched up North Street to his mansion on Garden Court. For around an hour Hutchinson heard “furious knocks” at his door, watched as his windows were broken, and stayed hidden even as the crowd outside demanded to hear “from his own mouth” that he opposed the Stamp Act.[2] Although the protest outside Hutchinson’s home did not last long, his children were frightened and the family was on high alert. He took the next few days to report the rising unrest to British politician Richard Jackson.

Ironically, Hutchinson had in fact previously voiced his disapproval about the Stamp Act, and was positive that “some tragical events” would soon occur. As he noted, Massachusetts was already “in a deplorable situation” and warned Jackson that they were now facing a “dismal prospect before us as the commencement of the [Stamp] act approaches.”[3] Hutchinson’s words proved prophetic.

When the Hutchinson family gathered for lunch on August 26th, Thomas initially dismissed the rumors that his home would be attacked again. By dinnertime, the mood had changed. Hutchinson was informed that protestors had just ransacked the home of Benjamin Hallowell, the comptroller of customs and had stolen his money, clothing, and liquor. Although Hutchinson attempted to send his children away for their safety, his eldest daughter Martha refused to leave without him.[4] Luckily, the two were able to escape to a neighbor’s home just as the “hellish crew” carrying axes arrived. Hutchinson’s mansion was quickly overrun by protestors, who proceeded to tear away the wainscoting, doors, walls, and slate from the roof.[5] As protestors tore Hutchinson’s mansion apart, others trampled his garden trees, stole the family portraits, furniture, library collection, clothing, and £900 in cash. The crowd finally dispersed around 4 am, leaving Hutchinson’s home with nothing but “bare walls & floors.”[6]

Although modern historians disagree on who first instigated these protests, loyalist Judge Peter Oliver (Andrew Oliver’s brother) was certain that he knew the culprit: a 28-year-old North End shoemaker named Ebenezer Mackintosh.[7] Peter Oliver believed that higher-ranking Sons of Liberty members had ordered Mackintosh to perform “their dirty Jobs.” While it is true that Mackintosh participated in the August 14th attacks, there is no evidence that he was involved with the attack on the 26th. This did not prevent Mackintosh from being briefly arrested. Perhaps Peter Oliver’s claim that Mackintosh had total control of a “Mob of 2000 men” frightened government officials since they quickly released Mackintosh to avoid the possibility of retaliation.[8]

Peter Oliver was not the only political figure to strongly disapprove of “the Frenzy of Anarchy” that month.[9] Thirty-year-old John Adams condemned the attacks on Oliver, declaring that burning the effigy and destroying his home was “a very attrocious [sic] Violation of the Peace and of dangerous Tendency and Consequence.”[10] Still, Adams was sympathetic towards the protestors’ demands, noting that both the Oliver and Hutchinson families had gained immense power through nepotism. He understood how these families had “excite[d] jealousies among the People.” Adams also worried: could the “ascendancy of one Family” create a “foundation sufficient on which to erect a Tyranny?”[11]

Local newspapers added further political commentary and discussion about the protests, with striking contemporary parallels abounding. When the Boston Gazette Country Journal described the August 14th protests, they claimed that many of the participants were not locals from Boston but rather outside instigators, “many having come from Charlestown, Cambridge and other adjacent Towns.” The Boston Gazette suggested the effigy of Andrew Oliver could have “originated in Cambridge.” Their evidence? A pair of “Breeches” worn on the effigy looked similar to a pair “a Gentleman of that Town [wore] on Commencement Day.”[12]

Surprisingly, the Boston Gazette made a distinction between the August 14th attacks and the later attacks on the 26th. According to the paper, “most people seem dispos’d [sic] to discriminate between the Assembly on the 14th… and the unbridled Licentiousness of this Mob.” The writers of the Gazette believed both protests had “very different motives, as their Conduct was most evidently different.”[13] Interestingly, Thomas Hutchinson believed something similar. When describing the ruins of his home to Richard Jackson, he noted that “the encouragers of the first mob never intended matters should go to this length.”[14]

Debate over acceptable and unacceptable forms of protests is as relevant today as it was in 1765. The Boston Gazette’s response to the August 1765 protests is quite similar to how many today have condemned the violent protests. While the writers of the Gazette acknowledged that sometimes “the Cause of Liberty requires an extraordinary Spirit to support it,” they could not agree with the protestors’ methods. “Surely the pulling down Houses and robbing Persons of their substance especially when any supposed injuries can be redressed by Law,” they concluded, “is utterly inconsistent with the first Principles of Government.”[15]

As historian Alfred Young notes, the Sons of Liberty wanted to distance themselves from what they viewed as unruly mob actions. After the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, the Sons of Liberty celebrated their success by focusing on “the allegedly peaceful action of August 14, disavowing the destructive violence of August 26.”[16] On the fourth anniversary commemoration on August 14, 1769, John Adams recorded in his diary he dined with over 350 Sons of Liberty at a tavern in Dorchester.[17] Although Adams does not mention Paul Revere, we know from other sources Revere did attend this celebration.[18] As the Boston Gazette reported, the day’s celebrations started at the site of what was now known as the Liberty Tree, where Andrew Oliver’s effigy had hung four years earlier. Although the Gazette had denounced the attacks of 1765 at the time, now they celebrated the anniversary as a day where the “TRUE SONS OF LIBERTY” joined in “constitutional opposition to illegal, oppressive and arbitrary Measures at home and from abroad.”[19]

After Thomas Hutchinson’s home was destroyed, he stayed briefly at Castle William and later moved with his family to his larger estate in Milton. During this time, Hutchinson worked towards getting a reimbursement from the Crown. He recorded the damage to his home and possessions in a detailed document that illustrated his wealth and class. In one section of the document, Hutchinson estimated that he lost £3 worth of apparel attributed to “Mark (a negro).”[20] In total, Hutchinson calculated the protestors destroyed £2,200 worth of property. By June 1774, Hutchinson sailed to England, a defeated man. Just nine years after the protests against the Stamp Act, Boston had irrevocably changed as a result of the cumulative impacts of the Boston Massacre, the Tea Party, and the town’s ongoing occupation.

While they could not predict what effect their efforts would have at the time, people across America continued to protest. They organized, debated, and fought back against what they viewed as an escalating, authoritarian force that threatened their families, their livelihoods, and their economy. As the last few weeks have shown, protests are still an integral part of how Americans can make change. Although some changes can seem frightening and even dangerous, it is important to reflect that Loyalists and many ordinary citizens believed the changes proposed by the Sons of Liberty were dangerous, too. Just as the Sons of Liberty could not foresee how their actions would be viewed 255 years later, only time will tell how today’s protests will be remembered.

Nina Rodwin is an interpreter at the Paul Revere House

Works Cited

[1] Thomas Hutchinson to Richard Jackson, August 16 1765.

[2] Thomas Hutchinson to Richard Jackson, August 16 1765. Ibid.

[4] https://www.geni.com/people/Thomas-Hutchinson-Col-Lt-Gov-of-Massachusetts-Bay/6000000006348524045

[5] Thomas Hutchinson to Richard Jackson August 30th 1765

https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/2532

[6] Ibid

[7] http://boston1775.blogspot.com/2011/11/ebenezer-mackintosh-captain-of-south.html

[8] Peter Oliver’s Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View

[9] Ibid.

[10] MHS John Adams Diary August 15th 1765.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Boston Gazette and Country Journal 19 August 1765

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/1/sequence/171

[13] Boston Gazette and Country Journal 2 September 1765

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/1/sequence/182

[14] Thomas Hutchinson to Richard Jackson August 30th 1765

https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/2532

[15] Boston Gazette and Country Journal 2 September 1765

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/1/sequence/182

[16] Alfred Young, Gary Nash, Ray Raphael. Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals and Reformers in the Making of the Nation

[17] John Adams August 14 1769

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-01-02-0013-0001

[18] https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=8&mode=large&img_step=1&

[19] Boston Gazette and Country Journal 21 August 1769

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/2/sequence/677

[20] Such Ruins Were Never Seen in America

https://www.colonialsociety.org/publications/3297/such-ruins-were-never-seen-america-looting-thomas-hutchinsons-house-time-stamp