Italian Immigration to America and Boston’s North End

If you have ever visited Paul Revere’s North Square home, it is hard to imagine the surrounding North End neighborhood without its distinctive Italian flair. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Italians were imagining a community for themselves in the North End of Boston; conversely, many prominent Bostonians were imagining an American community without immigrants. Between 1880 and 1921, 4.2 million Italians immigrated to America, many of them settling in ethnic enclaves in eastern cities like Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. Boston typifies the immigration struggle in America from 1880-1924 in that two competing forces existed simultaneously and in friction; many of the leading anti-immigration voices had connections to the city at the same time that many immigrants sought a better life in Boston.

In 1861, the disparate Italian states unified as the Kingdom of Italy. This political unification brought a period of long suffering for the people of southern Italy. Beginning in the 1870s, taxes on wheat and salt disproportionately affected farmers and merchants in places such as Naples and Sicily. Unfortunately, a series of natural disasters made life even worse for those living in this economically vulnerable area. Blight ruined the grape crops in the 1880s, suppressing wine production, a cholera epidemic spread rapidly through the streets of Naples in 1882, and a series of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions killed thousands of people. These events created a growing feeling of hopelessness in this community, especially amongst the young men. Looking for a way to support their families, these young men, many of whom were illiterate, turned to America as a place to work and to send money back home. This process accelerated quickly. In 1877, 3,600 Italians immigrated to the United States. In 1890, 4,700 Italians settled in Boston alone.

Simultaneously, the Progressive movement was beginning in the United States. Based on social reform, it sought to address issues that arose with industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. Many arguments put forth by progressive reformers were rooted in social Darwinism. While social Darwinism has many facets, elite Americans most frequently employed the inequality of races. Using newspapers, many prominent Americans imagined and promoted an America of “white Americans of native birth and parentage.” Henry Cabot Lodge, a Harvard-educated Bostonian from Beacon Hill, was a disciple of social Darwinism and believed that America’s problems were “race problems.” As a long time United States senator from Massachusetts, Lodge championed immigration restriction as U.S. policy.

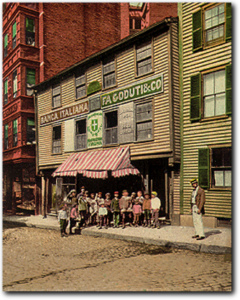

When Italian immigrants arrived in Boston, many chose to settle in the North End. Previous waves of immigration to the neighborhood included the Irish, fleeing the potato famine in the late 1840s, followed by Eastern European Jews fleeing pogroms and persecution. The neighborhood provided access to work on the waterfront, ideal for many of the illiterate, unskilled laborers that were arriving. Paul Revere’s former home served as a tenement for Italian immigrants and housed various businesses from an Italian bank to a produce stand. Italian Catholicism gained a foothold in the North End through Sacred Heart Church in North Square and the opening of St. Leonard’s Church on Hanover Street in 1899.

The people moving to the North End engaged in chain migration. Young men earned money to send to Italy so more family members could join them in America. This led to the formation of distinct ethnic enclaves within the neighborhood that preserved dialects and traditions from Italy. It also made cultural assimilation and Americanization less likely. Eager to preserve their heritage and identity, these individuals sometimes resisted the Progressive trend to become more American.

Several organizations were formed in Boston to help the new arrivals acclimate to their new environment, including the Civic Service House founded by Pauline Agassiz Shaw and the Society for Protection of Italian Immigrants in Boston in 1894. The Daughters of the American Revolution also commissioned a series of books entitled “How to be American” for those arriving from Italy, Ireland, and Eastern Europe.

Not all leading figures took welcoming positions, however. President Teddy Roosevelt once said that Southern Italians were the “most fecund and least desirable population of Europe.” In 1902, future President Woodrow Wilson wrote, “but now there came multitudes of men of the lowest class from the south of Italy … having neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence.”

Between 1900-1919, 2 million Italians arrived in America; around 68% of them were illiterate. Prominent Bostonians such as Henry Cabot Lodge advocated for a literacy test that would ideally end immigration to America. By 1910, 74% of Boston’s population was foreign born or had one parent who had immigrated. According to the government-funded Dillingham Commission, 32% of Italian immigrants to the North End were general laborers, with no trained skills, leading the neighborhood to take a “fundamental change for the worst.”

World War I and the United States’ entrance into the conflict in 1917 slowed immigration to the country. With the war’s conclusion, however, in May 1921, Congress passed the Emergency Immigration Act. This act created a nation-by-nation quota, capping immigration for a country at 3% of the individuals born in America by 1910. This act had devastating consequences for Italians wishing to settle in America, and specifically Boston. It cut Italian immigration by 82%, and imposed a 300-individual quota for Boston. On June 6, 1921, the SS Canopic, a steamship from Italy, docked at Boston Harbor with 1,040 individuals in third class alone. When authorities threatened not to let the passengers disembark, crowds gathered in protest.

Concurrently, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italian immigrants, were arrested and tried for murder in Dedham, Massachusetts. The North End of Boston, according to police, was increasingly the headquarters for the leading Italian anarchists in America, advocating for the violent overthrow of government. Such fears and tensions boiled over in front of the SS Canopic, requiring police presence to keep the protests under control. The passengers were allowed to disembark after being detained for days, but as a result “henceforth all excess-quota aliens would be denied admission and deported.”

In 1924, with Calvin Coolidge advocating that, “America must be kept American,” a permanent immigration act passed through Congress. Known as the Johnson-Reed Act, or National Origins Act, this legislation capped total immigration to America at 155,000 individuals per year. National quotas, based on the 1890 census, set entrance numbers at 2% of the U.S. foreign-born population for that nation. This act, while celebrated by men like Henry Cabot Lodge, had devastating effects in the coming decades for those attempting to flee the genocidal terror of Adolf Hitler.

While many prominent Americans, from Presidents to Senators, were imagining a country with little to no immigration, immigrants were busy making the best out of their circumstances upon their arrival to America. Many of these immigrants transformed cramped, tenement housing into single-family homes and developed businesses and community organizations that survive today, carving a place for themselves and their descendants in America. The cultural cachet of today’s North End is so heavily dependent on its rich Italian heritage, it is hard to imagine a time when this was not the case. That said, even the effort to save the Paul Revere House and open it as a museum was not without tension around how the home of an American hero could exist and function in a decidedly immigrant quarter. The fraught story of immigration in turn-of-the-century Boston is one of resilience in the face of powerful local resistance to change. Today, the North End of Boston is a neighborhood rich in traditions. The colorful parades, festivals, food, and music connect people to the past and allow us to reflect on the transformation of one neighborhood in America.

Mandy Tuttle is an interpreter at the Paul Revere House