“Missing” Revere Letter Returns to the Paul Revere House

By Emily Holmes

Editor’s Note: This Revere Express post is adapted from the Fall 2014 issue of The Revere House Gazette. It has been reformed for use as a companion piece to Monday’s post by Nina Rodwin.

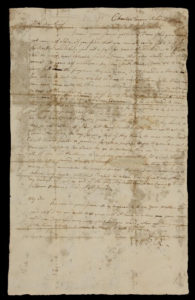

Shortly after the Siege of Boston began in the spring of 1775, Paul Revere took a few minutes to scrawl a hasty letter to his wife, Rachel. In it, he included details of his plan to get most of the Revere family out of occupied Boston. In the late nineteenth century, historian Elbridge Henry Goss transcribed this letter, then in family hands, and included it in the first full-length biographical work on Revere. Later researchers, from Revere biographer, Esther Forbes, to our museum staff, relied on Goss’s transcription rather than the original document when studying this period in Revere’s life. Historians did not realize that the original letter, a true gem of Revere and Revolutionary War history, was being preserved safely in private hands until unexpectedly, a Revere descendant brought it into the museum in 2011.

Perhaps because the letter’s inscription reads “My Dear Girl” and because the letter is signed “your loving father, P.R.” in a postscript, the descendants who inherited it had assumed that Revere intended it to reach one of his many daughters. A close reading, along with familiarity with the context, indicates that the intended recipient was actually Revere’s second wife, Rachel, who had likely not seen her husband for days, since he had left for his now famous midnight ride.

In the aftermath of the battles at Lexington and Concord, the British maintained their occupation of Boston and the militia began to surround the outskirts of the town. Under the circumstances it was not safe for even the daring Paul Revere to return home. Stuck outside the British lines working as a messenger for the Committee of Safety, Revere was no doubt privy to the plans of the Patriot leaders to lay siege to Boston. Knowing the rebellious colonists hoped to convince the British to evacuate the town by cutting off the constant supply of food and firewood normally delivered to the peninsula via Boston Neck, Revere surely worried about the effects of a siege on his trapped family.

It is unclear how the Reveres managed to smuggle this and other letters back and forth across the battle lines. Perhaps a few boats snuck across the Charles River under cover of darkness. There was no formal postal system in the colonies so it was not unusual for letters to simply travel from hand to hand privately, even under more peaceful conditions. Paper was scarce and expensive, even before war broke out, explaining why Revere combined two notes into one document and why most letters (including this one) were folded, sealed, and addressed on the outside without the protection of an envelope.

It was in this context that Paul Revere wrote to Rachel in late April with details of a plan, “I mean that you should send Beds enough for yourself and Children, my chest, your trunk, with Books Cloaths &c to the ferry.” In the eighteenth century “beds” referred to straw or feather stuffed mattresses rather than the wooden frames upon which they were sometimes placed. Revere promised to provide a house for Rachel and the children to escape to – if she could get a pass from the soldiers and get their essential goods out of Boston.

The one exception was Paul Revere Jr., the son whom he asked to remain at home “to be serviceable to me, your Mother, and your self.” As a 15-year-old Paul Jr. was not yet considered an adult, but with the advent of war he was called upon to shoulder the burdens of a mature man. Paul Revere hoped that Paul Jr.’s obvious presence in the house might deter any potential looters from destroying their home and its contents. In the letter Revere also asked Rachel to offer his shop to the silversmith Isaac Clemmons (a Loyalist who later fled Boston during the British evacuation in 1776).

Revere then cryptically asked Rachel to tell Paul Jr. to “attend to My Business and not be out of the way.” Could this mean more than making himself useful to Rachel as she packed up the rest of the family? It is possible that Revere intended to use his son not only to mind the shop and their home, but also to act as a spy inside the occupied town. Of course, it might also be interpreted as suggesting that Paul Jr. was prone to making himself scarce when help was required and in this case his father wanted him to be present and available to assist as much as possible. Just as it can sometimes be difficult to read a person’s intention and inflection via email or text today, in this instance, we wish we could fully understand the nuance and context behind his ambiguous wording!

Unfortunately, we can only speculate about how long Paul Jr. remained in Boston – was it only for a week or two? A month? Or for the entire siege? And was he entirely alone? Revere mentions three people- “Betty, My Mother, Mrs Metcalf” who might also stay in Boston. Widowed more than twenty years earlier, Revere’s mother, Deborah (Hichborn) Revere, is thought to have lived in (her eldest son) Paul Revere’s household until her death in 1777. Revere probably also provided a home for his sisters while they were unmarried. In 1775 that likely included at least one of his younger sisters, Elizabeth, who may have been called Betty, and possibly his older sister, Deborah (Revere) Metcalf, who had been widowed in 1763. Perhaps Revere took the presence of these three adult women (all over 30 years of age at the time) into account when he calculated the risk of leaving his teenage son behind in their home.

As noted in Nina Rodwin’s recent Revere Express post, we know that Rachel and the other six children (ranging in age from 5 months to 17 years) eventually joined Revere in Watertown (the temporary seat of the Massachusetts Government) where he rented part of a house for the duration of the siege. We also know that the British evacuation from Boston on March 17, 1776, allowed the Reveres and other refugees to return to their homes, almost a year after the siege began. Whether or not Paul Jr. lived there during the entire siege, the plan to keep their house and belongings safe succeeded. Luckily this letter that Paul and Rachel exchanged during the war survived and was preserved by family members for generations. The generosity of several donors and the Reynolds Family Trust allowed us to bring this very special letter “home” to the Paul Revere House in 2014, the very place where Rachel likely first received it in 1775.

Emily Holmes is the Director of Education at the Paul Revere House.