North End

The North End was one of colonial Boston’s three original neighborhoods. Separated from the rest of Boston by a mill stream, later by an elevated highway, and now by the Rose Kennedy Greenway, the North End has always considered itself to be somewhat apart from the rest of the city, and over the years has developed its own unique character.

The first English settlers in the North End built their houses along the waterfront, and from the earliest days depended a great deal on the sea to make their living. By the mid-18th century, the North End had become the most densely populated of any of Boston’s neighborhoods, and its residents included an eclectic mix of wealthy merchants, industrious artisans, transient mariners, and laborers in the many shipyards, warehouses, and wharves that lined the waterfront. Numerous church spires rose above the houses that lined the streets, and the squares were filled with the sights and sounds of a busy English commercial town.

The North End and its residents, like everyone in Boston, witnessed and engaged in the alarms, disruption, and general unrest of the Revolutionary War era. Significant events that took place in the North End in the 1760s and 1770s included the sacking of Thomas Hutchinson’s mansion on Garden Court Street during the Stamp Act riots of 1765; the murder of Christopher Seider on Middle Street a few weeks before the Boston Massacre; Paul Revere’s memorial “Illumination” of both young Seider’s death and the Massacre in the windows of his North Square home in 1771; and the meetings of the North Caucus at the Green Dragon and other taverns where the destruction of a few shiploads of British East India Company tea was planned in November and December, 1773.

In the aftermath of the Revolutionary War and with the creation of the new Nation, the North End gradually changed as older Anglo-American families moved into newer neighborhoods such as Beacon Hill and South Boston or other more outlying districts. Their houses were transformed into warehouses and sailors’ boardinghouses. For decades, the Reverend Edward Thompson Taylor, a former sailor turned Methodist minister, preached to sailors “in their own language” in his quaint “Seamen’s Bethel” on North Square (now the Catholic Sacred Heart Church). Significant numbers of old Yankee families held on for a surprisingly long time, however, giving the North End a highly picturesque and mixed feeling in the 1820s and 1830s.

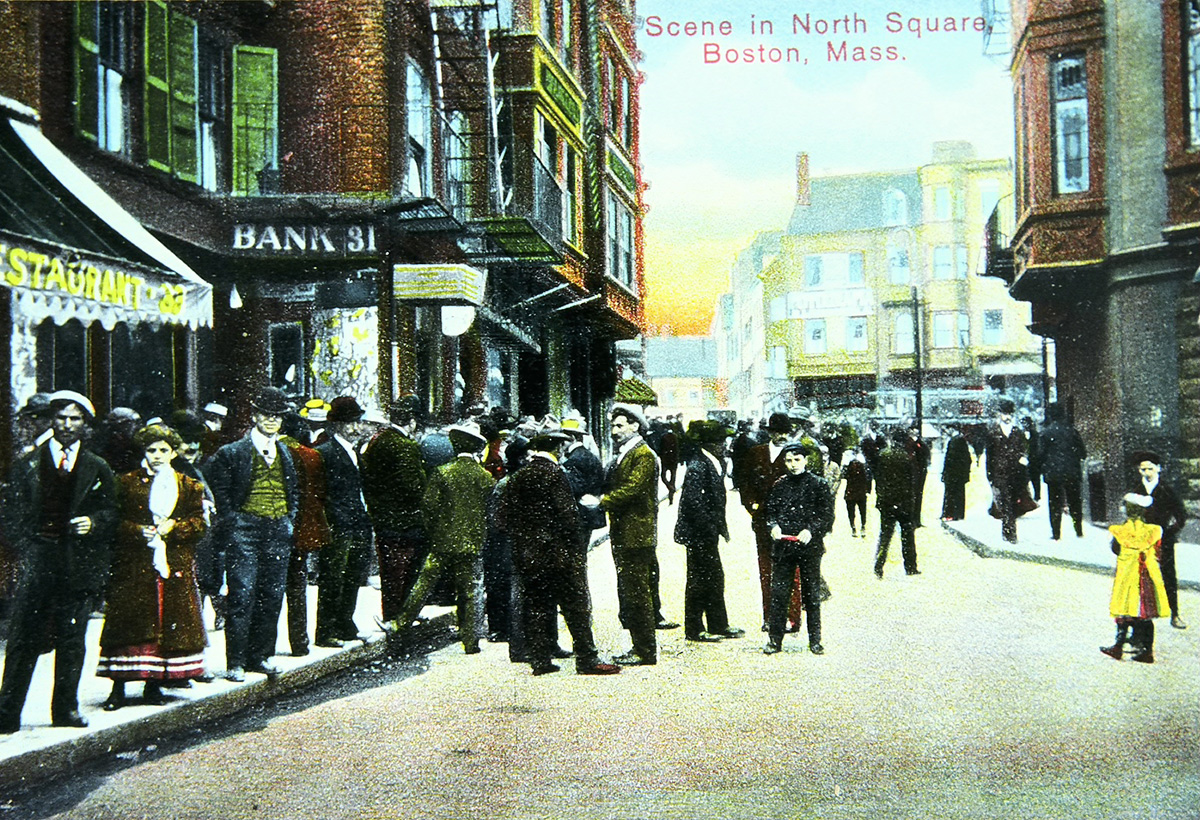

All of this changed rather rapidly in the 1840s, when thousands of Irish immigrants began arriving fleeing the “Great Hunger” in their homeland following successive failures of the all-important potato crop. The Irish rented cheap accommodations wherever they could often in waterfront districts, and took whatever work they could find, chiefly as day-laborers on canals and railroads, and as ditch-diggers. Irish women often found employment as maids and nannies in wealthy Boston homes. The Irish were followed by Eastern European Jews, driven out of their homelands by systematic persecution, militarism, and the threat of conscription into the army. Jewish immigrants settled throughout the North End, but primarily in and around Salem Street. Jewish entrepreneurs labored as itinerant peddlers and as shopkeepers in basement shops that lined North End streets.

To learn more about the neighborhood in the mid-19th century through archaeological evidence, visit the city’s online exhibit, A Tale of Two Privies!

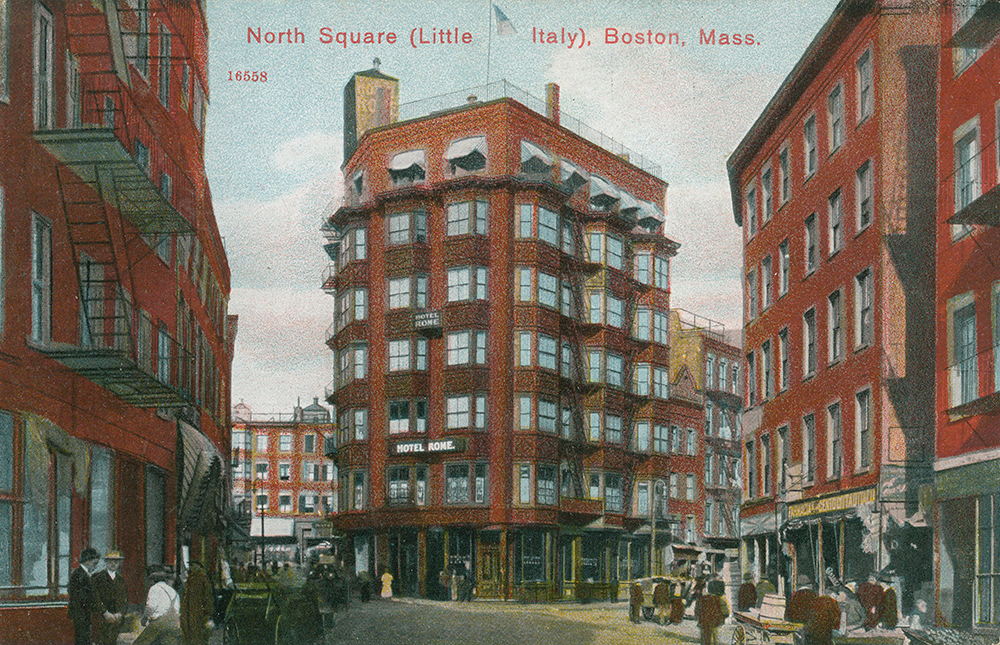

In the 1890s, large numbers of Italians began to arrive, mostly from southern Italy and Sicily, driven out by overpopulation, economic stagnation, and the collapse of local crafts as one result of the unification of Italy in the 1860s. By 1895, the North End had become one-third Irish, one-third Jewish, and one-third Italian. By the 1920s, it had become almost one-hundred percent Italian or Italian-American. Shut out from such secure jobs as working for railroads or the transit system, Italian immigrants obtained employment wherever they could, but frequently depended on padrones or labor racketeers to obtain work on farms surrounding the city (or even as far away as the Mid-west or Alaska!). The padrone system did allow many Italians to eventually become successful truck farmers, supplying cities with badly needed fresh fruits and vegetables.

By the 1920s, the North End had become congested and overcrowded, with over 40,000 residents, many of whom were very poor (the neighborhood now has about 10,000). Since the 1930s, however, the neighborhood has become more prosperous, in part due to historic sites like the Paul Revere House, the Old North Church, Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, bakeries, shops, and the many Italian restaurants. The North End today is a vibrant Italian-American neighborhood and a destination for tourists and Bostonians alike seeking insight into history or a pleasant night on the town.