Revere’s Silver Shop

Paul Revere’s silver shop was the cornerstone of his professional life. Although he became involved in other businesses, silversmithing was his earliest and most enduring pursuit. Revere began his career as an apprentice to his father. His earliest maker’s mark was the same as his father’s, and evidence suggests that they shared patterns for casting handles and other parts. The elder Revere died in 1754, before Paul was old enough to run the shop on his own. Exactly what happened at this point is not clear, as there is no documentation — the earliest surviving Revere silver shop records begin in 1761. By law, Paul Revere’s mother became the proprietor of the business. Since there is no evidence that she had ever been trained as a silversmith, normally she would have hired a journeyman (a fully trained silversmith who did not have his own business) to run the shop until her son was old enough (usually 21). Alternatively, she may have let her son and perhaps some of his brothers run the shop under her supervision. Whatever is the case, soon after returning from service in the French and Indian War, Paul Revere took over his father’s shop inheriting its customer base, tools, and good reputation.

Paul Revere had a large variety of customers. It is a misconception that he only worked for the wealthy. Although Revere made some large tea services for affluent persons, much of his work consisted of small sales to those of middling and lesser means. The shop made and sold over 1,000 personal items including buckles and clasps, buttons, rings, and beads. Revere’s silver shop books also record 414 repairs such as mending, cleaning and polishing.

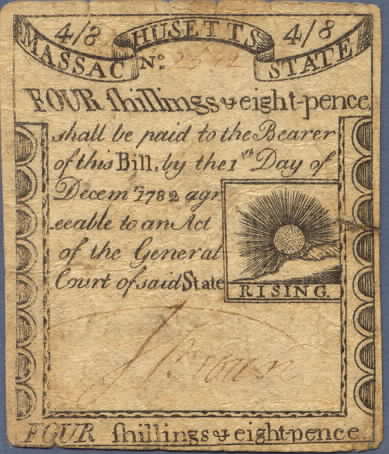

In addition to making silver objects, Paul Revere’s work as an engraver also played an important and lucrative role in shop operations. At his customer’s request, Revere engraved decorations on the silver such as elaborate inscriptions, monograms or family crests, for which he charged extra. He also used this skill to engrave copper and other metals for printing. On a small printing press in his shop, Revere produced thousands of prints, such as the money he engraved and printed for the Massachusetts government. He also printed advertising pieces such as labels for clocks and hats, as well as illustrations for books, magazines, and newspapers. Some of Revere’s mos famous engravings are his political prints, such as his depiction of the Boston Massacre of March 1770.

Revere’s business ledgers reveal that his shop was an active place. Its activities can be divided into two periods – before and after the American Revolution. There are two primary daybooks that survive for the silver shop, covering the years 1761-1783 and 1783-1797, although Revere worked before and after those years. The daybooks record the making of over 5,000 silver objects, and almost 24,000 prints. More items were produced after the war (4,210) than before (1,145). Around 1787, Revere entered into alliances with several saddlers and harness makers for whom he made over 1,000 metal fittings, such as bridle buckles and saddle nails. (These daybooks can be found in the Revere Family Papers Collection at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston.)

As the master of the shop, Paul Revere was responsible for both the workmanship and the quality of the metal. He trained a number of young men in the trade, including several family members. He also employed journeyman silversmiths. Revere’s personal involvement with fabricating silver in the shop was greater before the Revolution. After the war, the Revere shop excelled in working in the new neoclassical style, making fluted tea pots, butter boats, and creamers, but his shop also produced many more spoons, which were a standard form that Revere’s journeymen or his son Paul could make. In the 1780s, as his son Paul took charge of the shop on a daily basis, Revere expanded into other business ventures — a hardware store, foundry and eventually a copper rolling mill.

It is unclear what became of Paul Revere’s silver shop business. The last known piece from the shop was from the early 1800s. There are no known records of the shop being sold, liquidated, or continued by his descendants. It is not mentioned in Revere’s will.