Wait, Did You Say 16 Kids?

By: Rachel Mead

Visitors to the Paul Revere House are often amazed to learn that Paul Revere had 16 children. No, that is not a typo. He married his first wife, Sarah Orne, on August 17, 1757 when he was 22 and she was 21. They started having children within a year. Deborah, the eldest, was born only eight months after their marriage: “quick enough to start the gossips counting on their fingers, but not quick enough to give them any scandal.”[i] Every even year, for the next 14 years, Sarah gave birth again.[ii] After Deborah, there were seven more: Paul, Sarah, Mary, Frances, Mary again, Elizabeth, and Isannah.

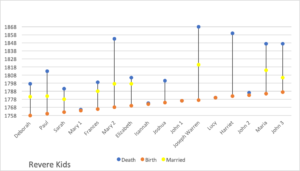

Click the image above to see more in more detail the birth, marriage and death dates of the 16 Revere children

Sarah Orne Revere died at the age of 37 on May 3, 1773, about 5 months after Isannah was born. We do not know whether the birth had anything to do with her untimely death. We do know that childbirth was not the main cause of death for women. The most common cause of death for all demographics in the 18th and early 19th centuries was disease, in a time with neither antibiotics nor a developed understanding of germ theory. While we do not have a cause of death for all the Reveres, several of those whose information was recorded were connected to a specific illness. For instance, Rachel Revere died in 1813 at the age of 68 of a bilious cholic.[iii] The notice in the paper called it “a short, but distressing illness.”[iv] Of the children for whom a reason is recorded, Joshua is listed with “a pain in the chest”[v] at 26, Paul of consumption at 53, Harriet of “disease of the heart” at 77, the second Mary of dysentery at 85.

The life span for Revere’s children was variable, with five children dying in early childhood, and another five making it to at least 60. So, while infant mortality was quite high, life expectancy was not universally low. One could live long enough to die of “old age,” like Joseph Warren at 91. And while several of Revere’s daughters died during what were potentially their childbearing years, neither Deborah, Sarah, Frances, nor Elizabeth have childbirths recorded soon before their death. While it is possible that they died from miscarriage, or contracted an illness during a previous childbirth, we cannot say for sure that childbirth killed any of Revere’s children, just like we do not know Sarah Orne Revere’s cause of death.

When Sarah died, she left a very young baby, Isannah, behind. Paul had to find someone to help take care of the baby and the six other children. According to family tradition, Paul met Rachel Walker in North Square, liked her, and asked her over – and then her interest in and pity for Isannah brought her back to stay.[i] The baby died in mid-September, but by that point Paul and Rachel had established a bond. They were married on October 10, 1773. Rachel also had eight children: Joshua, John, Joseph Warren, Lucy, Harriet, another John, Maria, and a third and final John. Unlike Sarah, Rachel lived until the age of 68, long enough to witness the birth of at least two of her grandchildren.

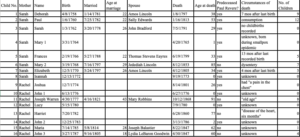

Click the image above to learn more about the Revere children including birth, marriage and death dates, number of children, and spouses.The Revere children experienced varied lives. Even though they all had the same father and all likely came through the house at 19 North Square at some stage in their lives, they were born over a period of 29 years and thus grew up under differing circumstances. Over the decades between the birth of Deborah and the birth of John, much changed for Paul Revere and his family. He lost a wife, and his children lost their mother. Paul’s own mother Deborah Hichborn, who had lived with his growing family since his marriage to Sarah, died in 1777. The family experienced the joy and growing pains of adding children, in-laws, and grandchildren, but also the heartbreak of losing five young children. And notably for his children’s quality of life, Paul Revere became much wealthier by the time his youngest children were born. In 1781, Revere described his state in a letter to his cousin as “in middling circumstances, and very well off for a tradesman.”[1] This description came years before his most financially lucrative businesses, however: the foundry he opened in 1788 and the copper rolling mill in 1800.

As a result of his late-life business ventures, Revere’s younger children had different opportunities than their older siblings. The older girls were educated at home and married Revere apprentices and business associates. On the other hand, Harriet and Maria, his younger daughters, attended boarding school. Harriet was the only Revere daughter to live to adulthood and not marry. Maria lived a life of adventure, marrying the French-born planter, merchant, and diplomat Joseph Balestier with whom she moved to Singapore. Revere’s older sons joined him in business after going to writing school for their primary school years. Paul Jr. was in the silversmith business, and Joseph Warren ultimately followed his father into his foundry and copper ventures. The youngest Revere, John, went to Harvard and then Edinburgh for medical school.

Revere’s large family allows for an examination of several misunderstandings about life in the 18th and 19th centuries. The comments visitors make when they hear about Revere’s 16 kids run the gamut from pity to lewdness. People often bring up a lack of birth control, cultural expectations to produce large families, or morbid overproduction to make up for high infant mortality rates. While these are all reasonable assumptions based on what we are taught about history, they simplify the complexity of the past to the point of inaccuracy.

Large families were common and often desired. Paul came from a family of 12 children. In all likelihood, he wanted a full and lively household as well. In 1786, the year before his last child was born, Revere wrote a letter to his cousin John Rivoire in Guernsey. Esther Forbes quotes the letter, editorializing a little to emphasize Revere’s interest in a having many children: “‘I have begun to think,’ he goes on sadly, ‘I shall have no more children. I have had fifteen children and six grandchildren.’”[2] And though the Reveres were probably not surprised that they lost 5 of their 16 children before the age of 5, it is unlikely that this is the reason they wanted a large family.[3] The loss of each child deeply mourned; upon the death of his 14th child, the second son named John, Paul wrote to his cousin that the family had “lost one of the finest little boys that ever was born, two years and three months old, named John, for you.”[4]

Revere’s children also had very different numbers of children, suggesting that neither social pressure nor familial norms provide adequate explanations for large families. Sarah, who married young at 16, had no children in 13 years of marriage. Maria had only one.[5] Of the other seven with kids, six had a number of children ranging from four to nine, and Paul Jr. had the most with 12.[6]

The idea that people lacked knowledge about conception and birth control is unfounded. Humans have been using methods of contraception for thousands of years, even if some of those methods were unsafe or unreliable. Fertility awareness methods were used by African and Indigenous people in colonial and early America as well. One of the most widely-used methods was breastfeeding, which is somewhat effective in preventing ovulation.[7] It is possible that this is how Sarah spaced out her pregnancies so evenly.

Paul Revere’s family was large, even for the time. In part this is because he had two wives and Rachel was many years younger, allowing him to father children over a nearly 30 year stretch. He had 16 children, 11 of whom survived to adulthood. Then, he had at least 51 grandchildren, and over 100 great-grandchildren.[8] Revere’s children represent a variety of possible outcomes for white, middle- to upper-class Bostonians in the early Federal period, whose experiences ranged from their father being a struggling artisan to a successful mill operator. Their lives were much more interesting and complicated than how old they were when they died, who they married, or how many children they had. But for many of them, especially the women and those who died young, that is all the information we have.

Rachel Mead is a former interpreter at the Paul Revere House

[1] Forbes 372, Paul is probably referring to his trade as a silversmith, although he did many other things!

[2] Forbes, 375

[3] Although, perhaps bolstered by the usefulness of many children to a tradesman who wanted apprentices.

[4] Forbes, 375

[5] Two, according to familysearch. Nielsen doesn’t include an “Eleanor Balestier, 1817-1818:” https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/L1C8-185

[6] Depending on how you define your families. After Deborah’s death, her husband Amos Lincoln remarried to her younger sister, Elizabeth. With nine children by Deborah and five by Elizabeth, Amos, then, fathers more of Paul Revere’s grandchildren than Paul Jr.

[7] “A History of Birth Control Methods.” The Katharine Dexter McCormick Library and the Education Division of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, January 2012. https://www.plannedparenthood.org/files/2613/9611/6275/History_of_BC_Methods.pdf

[8] He raised several of his grandchildren, particularly the children of his daughter, Frances. Frances’s husband Thomas Eayres was mentally ill and scared her, and they separated. Frances died shortly after, and Rachel and Paul were left to care for the children and provide for Thomas. Revere knew several of his great-grandchildren as well, including Maria Revere Curtis whose needlepoint sampler hangs in the house.

[i] Forbes, Esther. Paul Revere and the World He Lived In. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969: 185.

[i] Forbes, Esther. Paul Revere and the World He Lived In. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969: 58.

[ii] Donald M. Nielsen, The Revere Family, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register Vol 145, No 4. According to Nielsen, at least. Forbes disagrees on the birth of Sarah, the Reveres’ third child, and says she was born January 3, 1763, while Nielsen says 1762. This could be a case of a mistake due to dual dating, accounting for the difference between old and new system dates. It is worth noting that Forbes and Nielsen agree on other January dates, so it could simply be a misprint. There are quite a few dates on which Nielsen and Forbes differ, though. In this I have deferred to Nielsen’s more recent research.

[iii] “A Daughter of the Revolution: Rachel Walker Revere Writes to Her Husband, Paul Revere, in the Aftermath of His Famous Ride.” Massachusetts Historical Society, October 2009. https://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/a-daughter-of-the-revolution-rachel-walker-revere-writes-to-her-husband-paul-revere-in-the-aftermath-of-his-famous-ride-2009-10-01

[iv] Forbes, Esther. Paul Revere and the World He Lived In. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969: 450.

[v] Forbes, Esther. Paul Revere and the World He Lived In. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969: 418.